“Friendship is the hardest thing in the world to explain. It is not something you learn in school. But if you haven’t learned the meaning of friendship, you really haven’t learned anything” – Mohammad Ali

Who can say how friendships are made? Sometimes they are forged through family connections. At other times they are a result of shared interests. Often they are a consequence of necessity. Once in awhile they are a result of pure happenstance.

Happenstance is my recollection of how I became friends with a young girl about two years older than I was. I was about nine years old and I lived in Victoria BC with my mom, dad, two brothers and two sisters. We lived on Carnarvon Street in an area called Saanich, close to Mount Tolmie and near to what was called the “Normal School”. I remember thinking that living close to anything named normal was likely good and probably was an omen for a positive future. It was years later that I came to understand that a normal school was a place to train to be a teacher!!

Our Victoria street was not paved with cement but rather was an asphalt covered surface. Devoid of sidewalks it did not deter me and my friends from running door to door or hopping on our (motor-less) scooters. We played tag on the green lawns that our fathers had created by seeding the soil and carefully watering it over a summer season. Between the front yard and the blackened street was a large ditch. The neighborhood dogs enjoyed scampering up and down those gutters and lapping up the runoff water that gathered there after a few days of rain.

On one warm spring day I was cruising around on my CCM red two wheeler bicycle. My bike had white fenders complete with a large silver bell my dad had attached to the handle bars. It was early morning and the street was unusually quiet, perhaps it was a Sunday when the neighbors were at church or cooking an early morning breakfast of bacon and eggs.

I was happily riding around even daring to go one block beyond the two block radius my mother had limited my cycling to. On the outskirts of my biking boundary another cyclist overtook me. She had a green three speed bike and applied her brakes as she came up beside me. She looked exotic, wearing colorful peddle pushers and a ruffled white top. Her head was covered by a large scarf tied around her head and fashioned in the back – gypsy style and not a hair fell lose. We met several times after that day and I looked forward to connecting with this striking older girl.

I remember enjoying shared times with this worldly new-found friend. She told me wonderful stories about how her parents let her eat all the chocolate and ice cream that she wanted and she really only went to school half days. I had never heard of the school she attended but it was close to the Royal Jubilee Hospital where my mother had my young sister, Margaret Anne. She said her teachers were called tutors.

One of her most memorable tales was one that I thought she had certainly fabricated. She asked me if I knew where babies come from. I confidently replied “Yes, from my mommy’s tummy!” My sidekick had a good laugh that I thought was rather rude. She proceeded to fill me in about the “birds and the bees.” I was shocked and for sure in disbelief. My dad and mom do what? Sounded more like a bathroom story than the truth about the facts of life.

I told my mother about my new friend but did not divulge the part about “Where babies come from”. But when I shared her name with my mom and that she wore this amazing head scarf my mother stopped short. It seemed Mom knew my new found pal. She said my new confidant was very sick and that she had been in the hospital several times. The headscarf was a way to hide how ill she was. I was too young and naive to understand the implications what my mother was saying. It was a happenstance friendship that began to teach me about the realities of life. Friendships are precious. Treasure every moment you share with your friends.

I just told you a sad story about one of my early friendships. I tell it not to bring you down but to set the stage for an appreciation for affection and strong connection.

Certainly these Covid times are trying, challenging and overwhelmingly frustrating. Often I find it difficult to discover some positiveness. One of the most constructive outcomes of this long lasting pandemic is the friendships it has forged and solidified. Whether new or old, my friendships during COVID are strong and cherished.

About four years ago through friends that I met in Palm Desert, I learned to play a card game called canasta. It is a game that was developed in Uruguay 1939 and it blends Bridge with gin rummy. The current version is more complicated that the original variety although some of my bridge playing friends would beg to differ! At any rate the game was fun in person when playing with “real” cards and I met many new people who have become my friends.

Covid brought all in person direct contact to a sudden and discouraging halt. Our real life communication was replaced by zoom calls, FaceTime and all manner of technological connection. To satisfy my canasta addiction I became reliant on an online site called Canasta Junction. Many of my Palm Desert card playing companions signed up the canasta app. Soon I was playing online at least three times a week. My desert pals often brought new people I had never met to our games. What an interesting outcome – meeting friends of friends through technology.

I have one long-standing Edmonton friend who is as equally addicted to Canasta Junction as I am – if not more! Like me, she competes against the computer and also plays with three of our Edmonton buddies every Wednesday. But what is unique about her is this. When my Palm Desert friends were looking for a fourth my Edmonton girlfriend stepped in. So for over a year now my pal has been playing with my Palm Desert group whom she has never met in person!! Through several sessions of online play per week, my Edmonton buddy has grown close to my desert chums.

With the help of Houseparty all the players are able to see each other and share conversation. People joke together and tease each other about the pace of play. We know each other’s family stories, each person’s aches and pains and what they are making for dinner. Recipes are exchanged and favorite series to binge on are shared. Connected through on line canasta. Who would have thought?

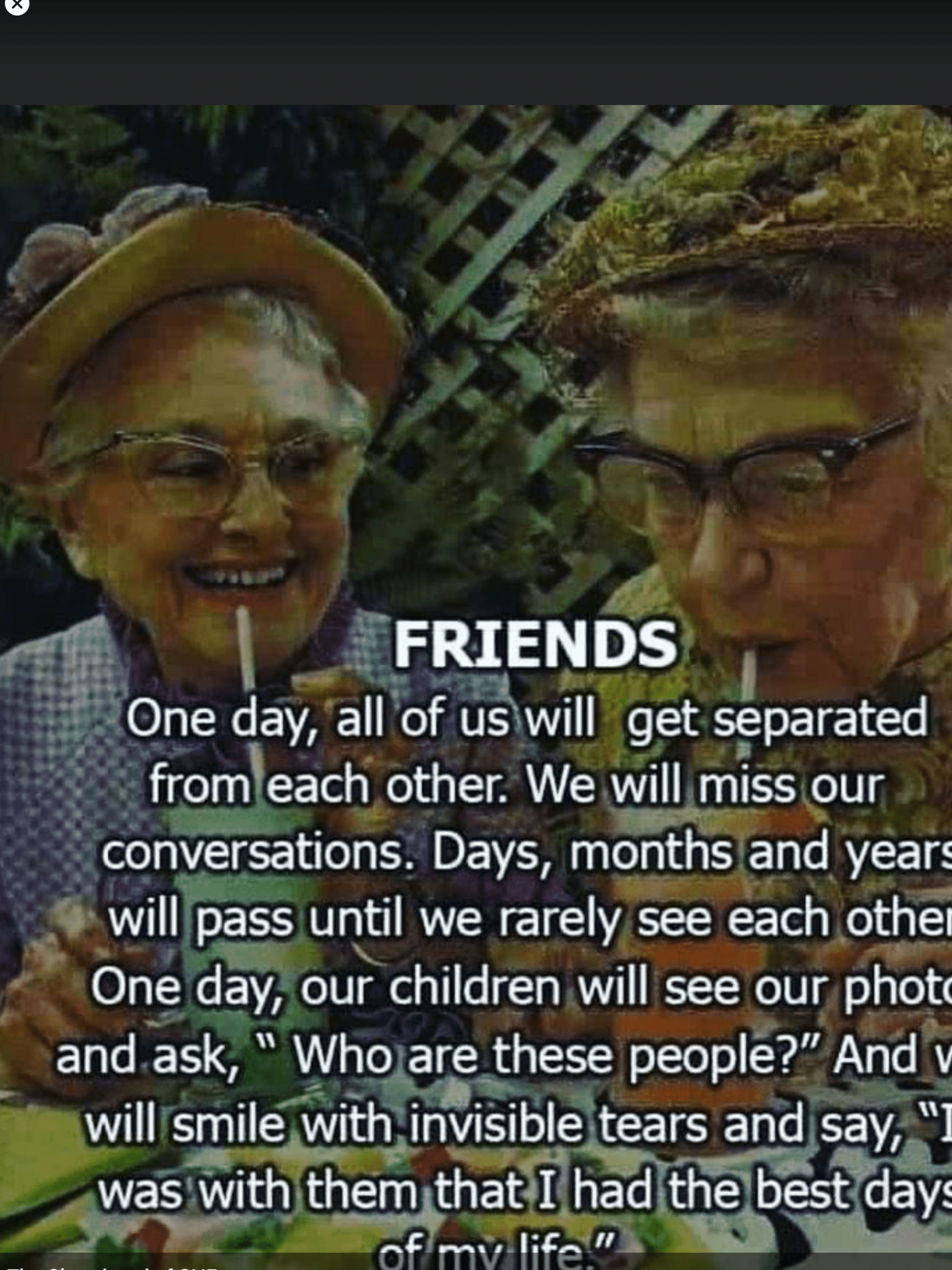

Houseparty has also been an important conduit to my long time Edmonton girl friends. We call ourselves “The Edmonton Girls” and towards the end of most days we connect online and touch base for about an hour. Not all of us are on all the time but for about six days a week we share Houseparty time. We rant about COVID realities and lament the old days. We analyze our Canadian politics and share anecdotes about our kids and grandchildren. We figure out the ills of the world and most assuredly we are all beyond brilliant. More importantly, this routine underscores how we value each other’s friendship and know we can count on each other.

It has been said that there are no friends like the old friends. Most certainly that is true and for me the pandemic has solidified those relationships. I also celebrate and cherish the new bonds the pandemic has created. “Friends are all we have to get us through life.” (Dean Koontz)

Sassy Blog